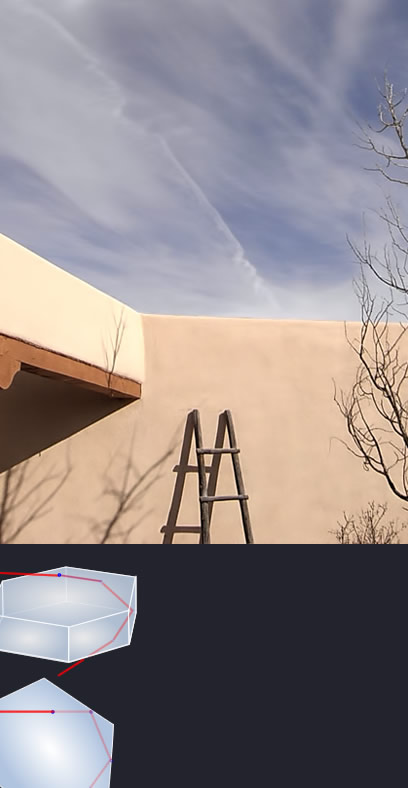

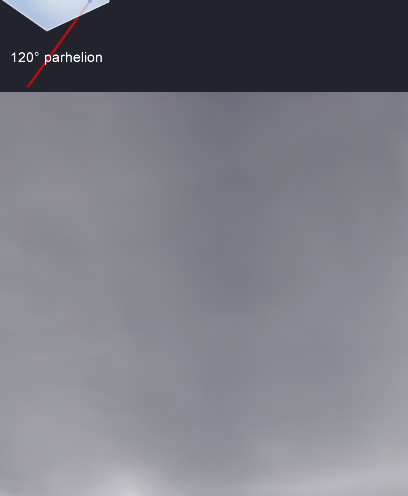

| Ice crystals in high cirrus produced the halos. Cirrus is composed of ice crystals (or supercooled water droplets) at all seasons and places on the planet. Halos are not confined to Arctic climes. The white arc curving across the sky is the parhelic circle. When complete it circles the sky at the same altitude as the sun and passes through it. In this case it was most likely made by horizontal plate crystals but it can also be produced by horizontal columns. Plate crystals definitely made the colourless parhelion 120° around the parhelic circle from the sun. Its generation ray path is compared at left with that of the more common 22° parhelion or sundog. Rays enter a crystal top face then reflect twice internally from vertical side faces before leaving through the bottom facet. The entrance and exit angles are equal and opposite so there is no net dispersion into colours - take away the internal reflections and the path is equivalent to looking through a plate glass window. 120° parhelia are white (mostly!) but always look for the close-by blue spot. Are 120° parhelia rare? Yes, because they demand higher crystal perfection than ordinary parhelia. The complex ray path is also best executed in thick plates or ones that have a triangular aspect - alternate sides long and short. Add to that - with their lack of colour - they are difficult to discern from a bright patch of cloud. In this later image the cirrus has thickened and the sun is dimmer - a weaker halo in more patchy cloud would be hard to see. |